|

From a young age I have loved making things, my earliest memory of this was building ships in the backyard with my Dad or go-karts from scrap plywood and disassembled bicycles. As I grew older I started building tree-houses (my earliest architecture next to the sofa fort) and more elaborate boats and go-karts. I enjoyed making Warhammer and scale models and in my teen years I discovered the possibilities of Balsa Wood and how to make my own aeroplanes.

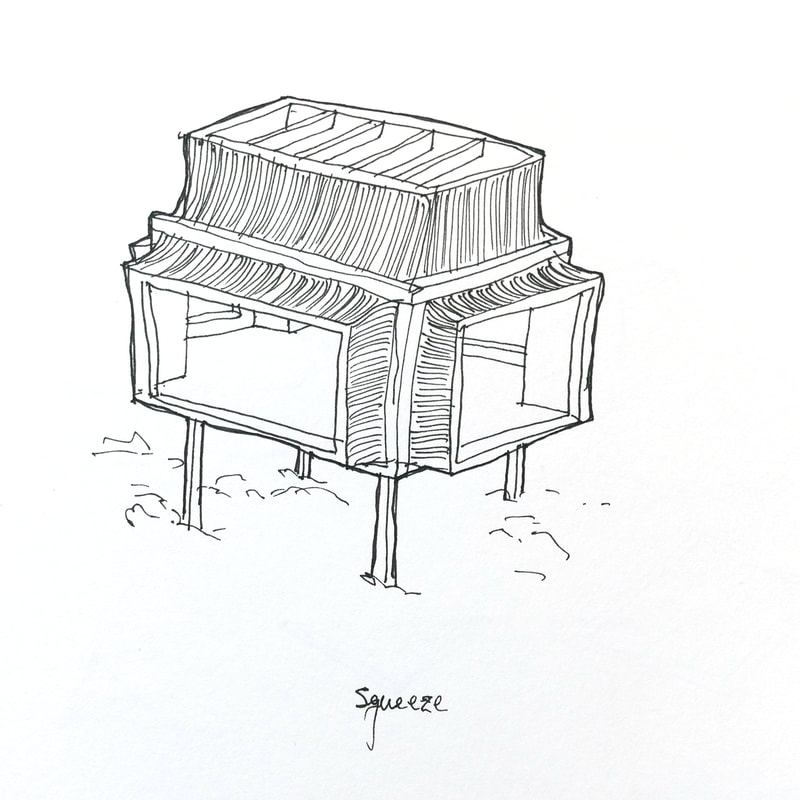

When I studied in Denmark I was exposed to a new depth of skills, material, tools and ways of thinking. We were taught that architecture did no belong just on the page and that to communicate we must also bring with us our ideas made physical. At the Aarhus School of Architecture there were incredibly skilled technicians, some who had spent years as professional furniture makers and all who brought patience and knowledge to any project I brought to them. I learned in the workshops there that my ideas could find new ways of expressing themselves through wood and metal and clay, in a more responsive way than paper or on a computer. I learned that there was no line between what was considered furniture or architecture, that all designs exists on the same spectrum of idea manifest in the physical world. Today with my architecture practice, my making skills are how I interact with the buildings I design. I do not see it that there is a point where my role stops and an interior designer or furniture store takes over. My ideas for space have strength and structure because I have thought of the objects that go inside them. It was true in the past that an Architect was a master craftsman and I wish to return that notion of craft and making intersecting with design and architecture.

0 Comments

To design with and not for.

Good design and architecture works with the land it shares and works with the people that interact with and inhabit it. Sometimes this thinking can become confused: "I designed this house for..." but it it is the buildings that include rather than exclude that create lasting space of joy. The difference is listening. There are many aspects to designing and building that need to be taken into account and we can get most of the way there by previous knowledge, intuition and skill. What makes a great building is having a process that asks questions and listens to the result. Listening requires an open mind and to not have a preconceived idea of what the outcome will be. Often I'll see buildings that clearly the architects had an image of what they wanted to design before they understood the property or its occupants and the result looks out of place, dropped in from somewhere else. Ask your clients what they truly want, how they want to live and what isn't working for them right now. Listen to what your clients are saying and keep asking questions. A good design relationship is built on listening and understanding. Listen to the property, where the wind comes from, where the water flow, to all the factors that make up a unique property. It is not hard to design a building but it requires effort to design a good building and listening is a step in the right direction. 1. Curves

Contemporary built environments are full of harsh angles and flat surfaces, yet our body and our natural environment is full of curves. Incorporating curvature into your design can increase the sense of comfort, spaciousness and welcome in your project. One or two curves in a project will have a dramatic impact on the experience of a space, introducing intrigue and playfulness. And they aren’t as expensive as one might think. 2. Natural materials Natural materials are typically hard-wearing and durable. Over the years, they acquire a patina that imbues character, whereas synthetic materials tend to break down and need replacing. For example, synthetic countertops vs. stone countertops. Natural materials communicate a quality of authenticity and integrity. You know that something isn’t just ‘surface level’ and will wear out, but will only get better with age. Additionally, many building materials contain synthetic chemicals that off gas over years into the spaces we live and sleep, polluting our bodies and environment with nasty chemicals. Home should be a safe and friendly place for our body. Using non-toxic natural materials in your home not only looks good but will make you feel good too. 3. Darkness Many contemporary buildings are inclined to maximise light with a lot of glass. This is an excellent way to improve the passive efficiency of homes and create connection with the outside world. Like with everything though, we need balance. A dark nook can be an intentional space for rest and respite. We all need to retreat into a cosy cave now and then. At the end of the day, our bodies actually require darkness to sync our circadian rhythm and give us a good rest. While light is intrinsic to a successful architecture, it is the interplay of light and darkness that create drama and produce spaces of surprise and reprieve. 4. Finishing Touches Everything you touch on a daily basis deserves thought and care. Fixings like door handles and staircase railings are typically bought or made towards the end of a build, when everyone is tired of talking about design. Yet, these details are what can make a good space, great. Thoughtful attention to fixings, like light switches and cabinetry, will allow them to disappear into the larger design concept. When tacked on haphazardly, they can command attention for the wrong reasons, interrupting what might be an otherwise seamless space. 5. The Big Picture When tough moments arise, it’s easy to lose sight of what you’re working towards. Design and build processes can be fatiguing and it’s easy to get bogged down by things like consent and planning. It's important to remember why you are building in the first place. A successful build requires a team effort. When it all feel like too much, sit down with the team and discuss what is working well, what isn’t and how to move forward. Designing any building is hard. That’s why it’s imperative that you work with highly skilled people who you enjoy working with. When the going gets tough, keep a good feeling and you’ll come out of the process with expanded capabilities, good memories and maybe a laugh or two down the line. Written Nick Dunning of OTO Group Architecture. As seen on Grand Designs New Zealand. In response to the essay “Standarder og Nuancer “ by Christine Bjerke.

There is an adage, design for all is design for none. Found in many places but of particular importance is the USAF studies of ergonomics in the 1950s and 1960s. What is now the basis for all contemporary studies in ergonomics, the USAF research sought to establish a universal design in their aeroplanes and uniforms. Bodies were measured and mapped, actions were closely studied and a standard for design was created. What ensued, however, was a design model that theoretically accounted for the 90th percentile but only suited a small range of humans: it forgot the simple fact that all our bodies are different and that when you try to design for everyone, you are in fact designing for no-one. True ergonomic design is adaptable, flexible and plastic to its users needs. Where we aren’t able to change the size of a fighter jet cockpit, we are able to shift the height of a table, offer clothes in different sizes and scale our needs appropriately. Where this falls flat is in the realm of architecture and urban design, where design has been thought in concrete terms and has been intended to cater for most people. When we cater for most, we miss the margins where design is of special importance. Inclusive design can be the field of including more people in the outcomes of good design or including more people in the process of design. Well intentioned but practically impossible. Why impossible? We are all different, we are diverse, we are unique. Inclusive design will always exclude a slim percentage of the population and that should be accepted as a good thing. Good design is all about intention, intention of what is the desired outcome and who are the users. What happens when we try to include every single person is that there are too many factors to include and in many cases, factors that are contrary to others and in effect cancel each other out. Successful inclusive design when done well is intentionally general and should be able to adapt to change and specific user engagement. That is not to say that it should explicitly exclude anyone, it should reference the people it cannot cater for and offer a plastic response so that it can still be used effectively. Examples of where this has happened is accessible staircases, where there isn’t enough space to cater for a legally sloped ramp. A case study is the integrated staircase/elevators of “Sesame Access”. As Christine touches upon in their essay, universal design lacks nuance in its approach, particularly when government standards are used. A broad brush is used where a finer tip is required. The thesis for the 2023 congress for UIA approaches the topic of universal design through the lens that accessible design is important to seek first, that “we will endeavour to reach the furthest behind first.” This, I feel, addresses the issue that universal design has much nuance and many facets but that looking at certain aspects of universal design we can start to build a better image of a large and complicated issue. And where does this leave us? It leaves us with the knowledge that to include is to also inherently exclude and that if done with intention and professionalism, we can recognise that there is still a long way to go in the realm of universal design. When we approach our projects we can seek to be more accessible, more inclusive and to look at who we are working with and for. We can design to be more flexible and adaptable to change and we can design with the knowledge that our buildings have no final state, that a good building is adaptable and that new user groups that we are not aware of yet will one day inhabit our spaces and that we can allow for them to be included and accommodated in the future. (The following is a translation from Danish and its accuracy has not been verified). By Christine Bjerke, Arkitekten 01 vol. 125 p. 20 The concept of universal design is often debated and challenged. Because there is at all an approach to design that can be universal, and don't you risk nuances being lost? The concept of universal design originated in the United States back in the 1980s. The architect Ron Mace, who was a wheelchair user, advocated, among other things, to bring accessibility into the US building code.¹ Mace wrote, among other things: Universal design is the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.2 In this way, universal design is closely linked with accessibility, and equal treatment is made part of basic human rights. It is of course a shared social responsibility that people are treated equally, but design and architecture, which create the physical surroundings, have a significant role and responsibility. In Denmark, around 700,000 - corresponding to 21 percent of the population - between the ages of 16 and 64 have a disability, also called functional impairment. Of these, it is estimated that 45 percent have what is described as a major disability, which corresponds to approx. 313,000 people.3 The figures are based on assessments, as it can be difficult to define a disability, and there is also no tradition of registering it in Denmark. Regardless of the numbers, architects have a responsibility to design with consideration for the diversity of bodies and minds in society. As studies carried out by the Institute for Human Rights show, it is still a challenge and often impossible for people with some types of disabilities to move around in many buildings. It is part of architects' basic ethical responsibility to be aware of how and when architecture includes and excludes. The country's schools of architecture have a central role, as universal design and accessibility are still not structurally and culturally integrated into architectural education. 1 2018, the Royal Academy received the Bevica Foundation's Accessibility Award as part of an ongoing collaboration that started in 2016. But in 2023, universal design and accessibility are still not an established and transversal part of the school's approach to architectural education. On the contrary, it is a focus that continues to be primarily raised locally by initiatives that take place at individual institutes. There is therefore a need for the education programs to focus much more on the lack of representation among the country's architecture students and teachers, i.a. of people with disabilities, who are underrepresented in the profession. The lack of focus may be one of the reasons why the architectural profession is no longer advanced when it comes to universal design. In addition, the approach to accessibility in architecture is often practiced in a very traditional way - as requirements and rules that must be complied with in accordance with current legislation in construction, rather than as an opportunity to fundamentally improve inclusion in architecture. Here, the architect has a responsibility to be critical. Both in relation to ensuring the inclusion of several perspectives and a reflected assessment of the subject's so-called standards. This applies, among other things, to the Neufert painting system from the 1930s, which partly still defines society based on a 'normative approach to body, mind and who uses which parts of the architecture. In Denmark, there are a number of institutions and organizations as well as individual architectural firms that have an active focus on universal design. This applies especially to Rumsans from Aalborg University, which is a knowledge portal that collects and presents multifaceted perspectives on universal design in a Danish context, but also with international perspectives. Another central focus comes from the scientific track "Design for Inclusivity" during the World Congress of Architects UIA with the title "Leave No One Behind", which will be held in Denmark in 2023. Here subject experts work with a focus on an intersectionality of e.g. gender, race, ethnicity, disability, age, economic background and species other than humans in the work with architecture. There is an overall need for us as architects to start celebrating architecture that works with nuances in universal design and care in relation to accessibility as a prerequisite for architectural quality. Christine Bjerke is architect MAA and study assistant at the Royal Academy. I do all of my own taxes. I do this to save money on accountants but there is a portion of 'I do everything else for. my business so I should be able to do this too' in there.

I never studied accounting. I don't really get tax. But this is the second year I've submitted a tax return and I'd like to share 3 quick lessons I've learned. 1. IRD are a lot friendlier than I'd thought. Whenever I give them a call, they sort out my problems right on the phone. They can even look at your screen while you are on the My IR website and guide you through how to fix your own issuses in the future. I always get someone friendly and engaged, we chat about our days, they help me out, I'm apologetic and they are understanding. Don't be afraid to give them a call if you have any questions. 2. Net income is different from Gross income. I vaguely remember having a lecture in Architecture school about net and gross floor area. Which is which I'm not entirely sure... Recently I did my tax return online and it doesn't ask for overall income and expenses separately, just net income. The way I read this was the income word and skipped over net. A net catches all right? Wrong. Net income is your total income with expenses deducted from this. 3. Expense reports need to be updated regularly. I need to submit GST returns every 2 months. That doesn't mean that I should sit down and collate my loose receipts every 2 months, I should dedicate a time in the week to do it. My current method is Friday morning at 10.30 I dedicate this time to inputting receipt data. It usually only take 15 minutes and saves a lot of time when the return is due. Also, expenses are a key part of running a business and collecting all the receipts you have related to the business will help keep your head afloat in the long run. Architecture studios are culturally entrenched in the design world, their function and presentation reaffirm architecture as a physical practice. Most studios like to feel they are unique but visit enough of them and they slowly meld in to one: apple computers, moleskine diaries, a bowl full of black fine liners, the core elements tende

If we take university as the root mold of a studio practice environment, we find rooms overflowing with desk space and tools. What are the bare essentials that you need to create solid work? -a computer of some sort $1000-$1500 -a notepad of another sort $100 -a drawing implement $50 -a recording device $500 The above list is everything that I need to create work. It is the bare list of things I take with me when I go hiking for a week and still want to work. Anything more is excess so let's break it down A COMPUTER OF SOME SORT Computers are funny things. They demand our attention at our desks and it seems our entire lives are dedicated to inputting and extracting information from them. Depending on your style of workflow, architecture can be quite computationally exacting. Software requirements vary from person to person but I've found the following to work best for my practice: -Sketchup- the fastest 3D modelling software available and there are free versions out there. Connect it with the mobile app and you've got a view anywhere display tool too. Sketchup requires little processing power compared to other 3D software. -Revit- For scale drawings and quick workflow, revit (our archicad if you're a mac person) ticks those boxes and requires little processing power. Skip autocad, illustrator or other 2D software, stick to BIM and reduce your work load. -Photoshop- Devote time to developing photoshop skills, you can save terrible renders with some clever textures. -Google Suite- Anything that google makes seems to work great. Instead of using Word etc, google docs and sheets are remotely accessible on any device and you don't have to worry about processing power or storage sizes. So that is pretty much it for day to day work, create some work, refine some work, invoice some people, email some people. The computer needs for the above are surprisingly minimal and we don't need the latest and greatest intel i9 processor and a grunty graphics card so lets talk how much this should cost you. An intel i5 from 2017 or later should last you many years, I do a lot of my work at home on an old intel i3 NUC from 2014 which runs all my software just fine. Don't get suckered into the faster computers, they are just more expensive and use more battery. Shop around for a second hand laptop, a lot of other people like to replace their machines every 12 months so take advantage of that. Make sure the battery is in good condition. Second hand windows laptops don't hold their value as much as the macbooks do. A 15 inch screen is ideal, settle for a 13 inch screen if you have to. A NOTEPAD OF ANOTHER SORT I've written down $100 as that is roughly how many $15 notebooks I go through in 12 months. I make my own notebooks but I've adjusted that for medium sized moleskines. Anything with decent enough paper for sketching ideas will work. A DRAWING IMPLEMENT The same applies here as I teach my students: no erasers allowed. I mean it is just good drawing practice but that will also save you enough money to buy a coffee or two. I use a $25 Lamy fountain pen with an ultra fine nib. I fill it up with $20 ink that is still going 2 years after buying it. I used to buy fine liners (starting with Steadtler at $8 a pen, UniPin at $6.50 a pen and Molotow at $6 a pen. The Molotows were the best overall regardless of price.) but the cost is too high for a year of drawing. Also, that plastic waste is insane. This is the bare bones for sketching and note taking, and everyone should have a host of drawing apartatus from University or stolen from their previous work. This is all I'd need to buy if my studio burnt down. A RECORDING DEVICE You'll need something to take photos of sites, record audio in interviews and maybe take videos of things for your website. If only there was a device that could do all of this for you... Instead of the $2000+ camera, we now have access to powerful phones that tick all these boxes. This cost might be a moot point as everyone has a smartphone but here I'd argue buying a bigger phone specifically for work and selling your old one is a good idea. I recently moved from a small Iphone SE to the hunky Samsung Note 8. I did this because the camera is fantastic so I leave my camera in the office more, it has a stylus for drawing quick sketches and taking notes, and it has good voice recording. It also has a much larger display so I can use it as a more effective display tool in meetings and don't need to spend more money on an iPad or other tablet. I bought mine second hand for $500. CONCLUSION So that is pretty much it. In future posts you'll see that I surround myself with a lot more stuff and my studio is heavily physical so the shear amount of furniture and apparatus is higher than necessary. In our digital world, there are so few boundaries to going out on your own, we don't need to buy expensive computers, drafting tables and other equipment to function. Semiotics involves designing in a way that uses a system of signs that contain an embedded symbolic meaning (Preziosi). Whether that be endemic to a particular culture or region is up to the architect and the viewer. Our minds work through associations so drawing parallels from the language we use can bring meaning to the viewer. Architecture uses a visual language which can be inherited from different aspects of life. It is this architectural language that we place meaning on and informs how we perceive elements.

Semiotics is our association with the familiar. For example, a small cottage may mean ‘home’, a row of romanesque columns means ‘strength’, Architectural language is used to either imply an idea or to draw a parallel to another idea and therefore associate itself with that idea. This was used on a large scale in the 1800’s in North America as new migrants aimed to ally themselves with the grandiose and powerful image of old Europe. Tall columns, delicate plaster work and rigid building elevations all aimed to push a connotation of buildings found in Rome on the viewer and therefore make them think of the building in front of them as something else. Metaphors found when we think of stress and depression are usually gloomy. We think of dark forests, emptiness or drifting underwater into unseen depths. Stress brings to mind heavy burdens, narrow vision and one thousand voices bombarding us from all directions. It is with these kinds of metaphors that we can design custom spaces for our clients. At OTO we ask our clients to provide a narrative of the emotions they see from their future home, maybe it is an image of a glass of red wine with the light coming through and casting red on the table, or the feeling of standing above the world and being projected out over the ocean. We can turn these images into physical space through careful and creative thinking. Let me just say this first off, I think 'Tiny House' has negative connotations. Tiny implies too small, less than what is wanted. Small is also negative but less so. Both draw direct comparison to their 'big' brothers, the sprawling 250m2 family home.

Tiny houses aren't tiny, they are efficient Tiny houses aren't tiny, they are comfortable Tiny houses aren't tiny, they are affordable Tiny houses aren't tiny, they are beautiful Tiny houses aren't tiny, they are ecological Tiny houses aren't tiny, they are characterful Tiny houses aren't tiny, they are inspiring We call the tiny houses that we design at OTO Group cabins or baches. If we look at traditional baches and cabins, they are compact, efficient and beautiful. If a large home is a rambling paragraph filled with grammatical inconsistencies, the small building is a succinct phrase that doesn't need any more words to say what it means. |